I spent September in a shell. My anxiety had rocked me shut. Passing in the mirrors I avoided was a person flush of color with darting eyes. I couldn’t figure out what was making me so anxious. I was haunted by the whispers of the ineffable. Something was about to go wrong, but I didn’t know what.

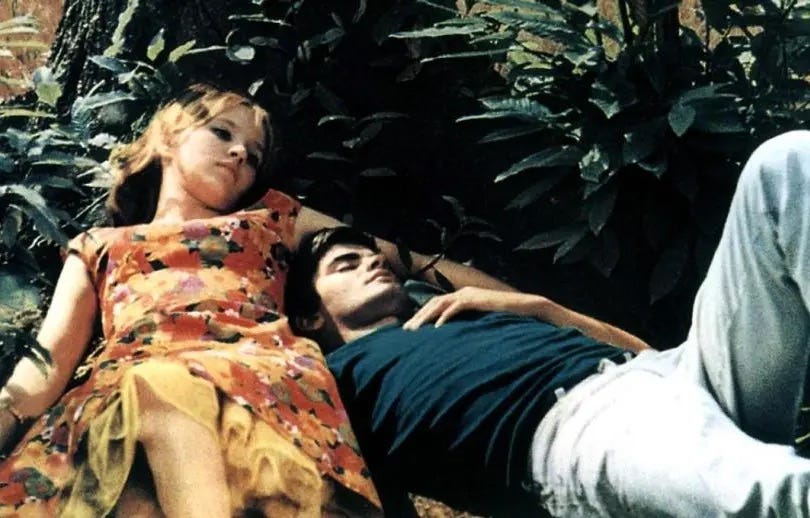

I looked for a source of my unease. My relationship was on solid ground — full of assurances, the sense of security that came from almost reaching the year mark. Together we had taken MDMA on the first night of that month. The moon clear and bright, we were finally back together after a month of an artist’s residency, a trip to Paris, and a tour. Cradled by ecstasy, my boyfriend and I spoke to each other on a picnic bench in language I was sure belonged to only us. Home to each other at last. In place and in feeling. I looked at him and knew, wherever the two of us went, we would be good at finding the other’s arms again.

We spent the next morning in the afterglow, watching movies on a blanket on his living room floor, kissing and eating decadent pizza. I couldn’t imagine myself happier. After the high came days of displacement. I couldn’t shake it. The chemicals in my brain struggled to regulate after. Serotonin dipping again when my boyfriend went away for another five days and didn’t have much time to call. He was busy, but I took it personally. I felt like a child as I sputtered over the phone how alone I felt, not even a timezone apart and only a few days of separation.

Our relationship had gone through its most trying month, but it wasn’t wholly responsible for the anxiety I couldn’t shake in healthy ways. There were other hard things. Since June, my writing had floundered. The nascent third draft of my novel stalled out. My belief in the project, in my ability to redraft faltered with each day that passed having written nothing.

Another bump—my best friend and I were weathering our first major conflict. Fragmented from the long, caring conversations that were at odds with our in-person hangs, tiptoeing, our interactions on the verge of tears. We struggled to imagine a future where multiple things could be true, putting our favorite maxim in the pressure cooker, testing to see if we could in fact learn to live with conflicting views.

I’d gone through a breakup earlier that summer with a different friend. There was no discussion. Over without another fight. The silence that followed came with the relief that for the first time in our friendship, I didn’t have to speculate if her distance was a response to some wrongdoing of mine. This time I simply knew it was.

I retreated to that old routine of self-abasement. The dregs of unhappiness that settled at the bottom of my otherwise overflowing cup flavored the whole thing. I did what other unhappy people did: I self-diagnosed. My outsized emotional reactions were symptomatic of something more sinister.

Soon that theory was clinically dismissed. I got a new therapist. She talked to me like I was a real person, a first for me. She recommended reading something other than www.doihavebpd.com — one such text was Attached by Amir Levine and Rachel S.F. Heller.

I had my suspicions about attachment theory. A few months ago, Miriam Gordis wrote an essay about her own (and others’) disbelief in the unstable scientific ground adult attachment theory stood on. People love pop-psychological explanations about why a shitty guy on Tinder won’t message them back. On a more base level, there could be no one-size fits all style for all people. My therapist concurred. She said the labels of the all-too-gender-adjacent “anxious” and “avoidant” were more damaging psychologically than freeing. It would have been better if the authors had chosen “purple” and “blue.” At the very least, we could use terms that didn’t feel like an accusation, rather than the lens of our differing worldview glasses.

Reading Attached, I definitely identified with some of the anxious attachment behaviors. This didn’t come as a surprise to me. Anxious attachment has had an ambient presence in most of my relationships (romantic and otherwise). What did surprise me was that confronting such strategies (particularly something called “protest behavior,” i.e. making yourself unavailable in response to a partner’s unavailability) was more embarrassing than liberating. I was ashamed to think that I’d resorted to such tactics in a mangled attempt to regain some power.

I’m not totally freed of my suspicion that all relationships are about power. My former poetry professor would claim that almost every poem was about power. At the time, I wasn’t convinced, but now, I think they were onto something. Writing is about power—an attempt on the author’s behalf to convince a reader that the language with which they are using to express themselves is urgent enough to put on the page. It’s not the only kind of power, but it is an originating source of it.

The powerlessness I had felt when anxious in relationships had, on the other hand, made it more difficult to find its originating source. The authors of Attached have some answers to that. Family dynamics, previous relationships, even interactions with friends. The key to not feel powerless is embracing your attachment style, and cultivate the belief that there is no “right” way to be attached (I’d argue that the authors seem to think there is one right way, of course, which is secure, but I digress).

I thought about what “security” meant. My boyfriend met many of the qualifications of the “secure” archetype. What security had he provided me? Let me count the ways. I trust him because I knew this person holds the ultimate power to devastate me, but would do everything in his power to not hurt me. When he tells me, half-asleep swimming in doxylamine, he would do anything for me, I believe this is included.

We’ve been sold the myth that the desire to dominate one another is in our nature. I think it’s simply untrue. Species have a greater tendency to ensure the survival of their fellow creature than they do to eliminate one another. Not to oversimplify, but it’s capitalism that has convinced us that a power struggle is natural, even healthy. You don’t need another woman in Brooklyn who has read The Communist Manifesto to tell you this is the wrong way to live.

Recently, I rewatched an episode of Girls when Gillian Jacobs’ Mimi-Rose confounds Adam with how little she needs him. When I first saw the episode in college, I thought the character was a nightmare. The highly-evolved, immovable woman who doesn’t inform her boyfriend of the abortion she gets until the next day. An epic fight leads to a quite romantic reconciliation, where Mimi-Rose informs Adam that she doesn’t need him, but she does want him. The episode ends with her faking sleep as he tucks a blanket around her shoulder. Something, she claims, she’s come to rely on.

The other day, I was at my boyfriend’s house working. He was out at work, so I set up office on the floor. I reveled in how close to him I felt in his space without his physical presence. I made myself useful between luxuriating on the couch and eating the leftovers. I hadn’t moved much for days, but was starting to get my energy back following a covid bout. We had cosplayed living together. It felt natural, our comings and goings. I wanted to leave the house tidy when I met a friend for dinner. But I have this habit of leaving glasses of water on the floor, where I tend to sit instead of the couch. As I was about to head out the door, I remembered the glass I’d set in the middle of the living room. My first thought was, I better go pick up that glass so he doesn’t walk in and knock it over then get mad at me! My second thought was, He has never gotten mad at you over something that silly, not even when you overflowed the bathtub the other day.

A deluge of relief to reframe his imagined reaction to no reaction at all. Even if the bathtub overflows, even if the fight extends into the morning, I’m trying to retrain my reflexes to be more trusting.

I’ve realized over the past few months that what’s familiar to me in romantic dynamics is a sense of unrest, and so I sought it out, when what I actually desire was peace .It takes time to rewire our thinking patterns. Sometimes it takes reading a pop psychology book and feeling mortified for behaving like a child who doesn’t know how to articulate their needs. Sometimes it takes only your imagination to work for you, not against you. I’m certainly one to jump to the worst conclusion instead of imagining the one where a person I love gives me the benefit of the doubt. My therapist taught me a new strategy. Rather than imagining the worst case scenario, propel your imagination as far as it can go into the future, where the best possible outcome has happened. Sometimes it just takes trusting the person you love will learn about your deepest hurt and not press their finger into an only-recently healed wound.

My therapist told me she didn’t see me as an anxiously attached person. My task was to stop thinking of myself as one. For right now, I have been able to give myself that grace.

I’m not ready to write about aspects of my chronic health condition that could impact the future. All that I will say is that my boyfriend and I made a decision that we’d take certain steps now so we could, in his words, fantasize about our future freely. We recently got the results. They were the best possible ones. We were able to admit that we’d spent the last month worrying about the bad news. We hadn’t stopped to imagine what this would feel like. The news our hearts didn’t dare to let us hope for.

The other night we lay in bed, in awe of the refuge we are for each other. A few weeks of sickness had allowed us to spend more quality time than we had in a while, talking, watching movies, cooking, showing each other videos of a baby pygmy hippo, and simply being together in quiet moments, waking up and knowing the other person was there ready to offer their care. We could give each other that security every day. Of knowing that it is a gift exchange, to love another person. A surprise, never an expectation—the best kinds are at least.

If anything, attachment theory is a framework. It’s not the missing piece to solve love and its various troubles. “Now that I know this is my behavior, I will find someone who won’t activate that behavior!” No, not at all. We trigger each other. If anything, it offers another painstaking attempt to understand how we can live with another person. There’s no science to that beyond helping each other survive, and if we’re lucky, help each other with more than that. Everyday learning what the other person needs to survive—one night a week sleeping alone, a good morning text, having company when sick—ensures the survival of the relationship. My boyfriend has said many times about my health, “There is no us if there is no you.”

So I’ll still leave the water glass on the floor. It won’t be a trap, even though sometimes I set those to get a reaction from you. To know you care. We learn to live together in our convalescence and our health. Our little songs of work while doing dishes, the sound of our rest. The house begins to settle, too. The life I always imagined, a home we make together even though for right now, we only lend each other our spare keys.

Beautfuil Text ✨🩷

this is so lovely. thank you for this.